Gilt Futurism

Borrowing from the future won't work if the future buggers off

Today the UK budget is being announced, and it’s expected to be a punishing one - higher taxes to pay for an ever expanding state. As with other economies, part of this spending is being covered by issuing government bonds (called “gilts” in the UK) - shifting some of the costs from current taxpayers to future ones.

In recent years, spending has grown massively whilst, due to productivity stagnation, the tax base has not grown to keep up. In this context, the Bank of England has been issuing gilts with maturities of 10, 30 and even 50 years. This is the period over which they will pay out interest, with the principal being repaid to the bond holder at the end. What I want to discuss here is how the progression of space colonies over that time will impact the ability of the UK government to pay - especially as colonies will pull in some of the very people that we rely on to increase GDP and provide tax revenue.

Talk of space colonies is often dismiss as mere science fiction, but in the context of debt that needs to be serviced on decade timescales, this is ridiculous. The idea of humans living on Mars is no more of a speculative flight of fancy than the idea of 50 year gilts being covered by taxpayers in 2075. You cannot price such gilts correctly if you dismiss the possibility of technological change over their lifetime.

Drawing on reasonable technological projections, I will outline what human expansion into space might mean for the UK’s economic future. Will space draw away the best and the brightest from the country to the point where it becomes hard to pay the bills?

There are a lot of unknowns here, and this is more a fun exercise than a serious analysis - more of a set of order-of-magnitude estimates - but I think readers will agree it is something that cannot be ignored in considering the future of our country.

After 10 Years

SpaceX is currently leading in space colonisation, by a fair stretch. Their Starship program will, when ready, allow huge amounts of people and cargo to travel to Mars. The readiness of it is a bit of an issue right now though.

Windows to launch to Mars open every 26 months, and the next one begins in November next year. SpaceX intended to use this window to launch their first test flights, to test interplanetary flight and entry, descent and landing on Mars. However, 2025 has been a year of setbacks for the program. Version 2 of the ship suffered a string of in flight failures, and has been retired in favour of the next version of both booster and ship - which will require a new launch tower. None of this will be ready for even its first suborbital test flight until the first quarter of 2026.

So I think it is now overwhelmingly likely that the first Starship test flights to Mars happen in 2029. If these tests go well, then a flotilla of unmanned ships will be sent in the 2031 window, to prepare ground for humans. If at this stage the ship is considered safe for flight, humans will follow in the 2033 window. Per SpaceX plans, this won’t be a small expedition; many people will go at once. Even with a further slip to the next window, we can expect humans going to Mars around the time our 10 year gilts must have their principals paid.

So at this point, it will be at least possible, although expensive, for ambitious and risk tolerant UK citizens to leave the planet. This is different from the emigrating to another country - as it is both more permanent, as return would be expensive and not even physically feasible for 3 years after departure, and because enforcement of things like exit taxes in not realistic over interplanetary distances. How are you planning to collect?

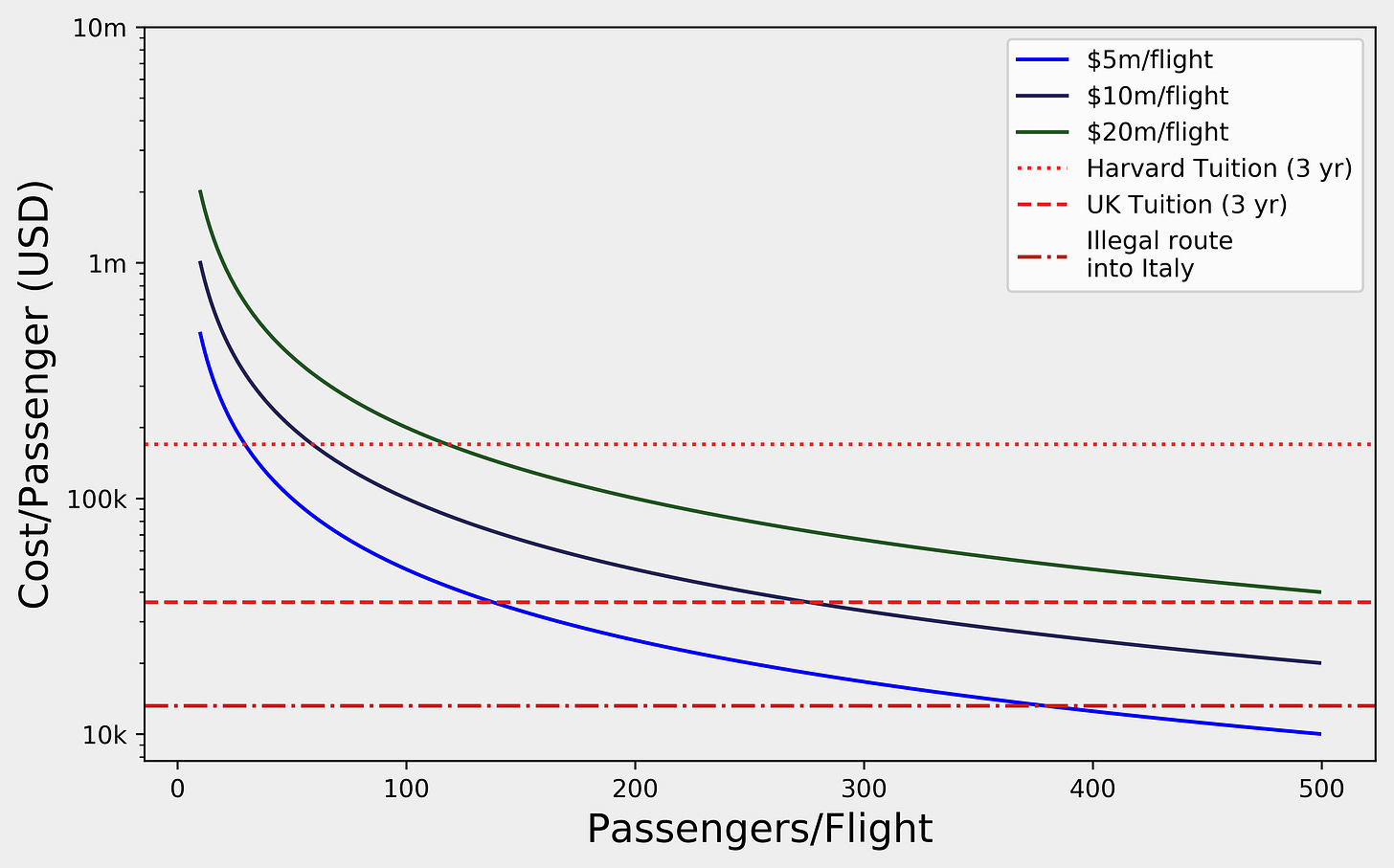

As mentioned, the cost will be high though - if a Starship can take 50 passengers to Mars, and requires 6 tanker flights to provide enough propellant for the trip, then those 50 passengers have to pay for 7 flights between them. I estimate the price per launch to be in the region of £15 million, so each passenger must pay £2.1 million. Not many people have this much cash around, and those that do are pretty well established on Earth. Perhaps financing arrangements would be possible, and there are plenty of well off people living in mortgaged £2.1 million properties in London - but at this stage it will probably be the case that the number who can go and who want to go is still going to be quite small. And given that 16500 high net worth individuals left the UK this year without a whole new planet to go to, a few hundred or thousand going to Mars instead of Dubai will not make things significantly worse.

Looking further out though, the situation will change more dramatically.

After 30 Years

There is an abundance of concepts for space colonisation, many of them with well thought out physics and engineering behind them. How can we gauge when such things are likely to be implemented, though?

The big constraint on what we can do in space is how much mass can be delivered to orbit, and just as under Moore’s Law the transistor count of microchips grew exponentially and drove the computer revolution, we are now seeing exponential growth in mass to orbit. Tracking this curve can give us insights into what to expect.

SpaceX is again leading in this; they are set to deliver about 3,000 tonnes to orbit using Falcon 9 rockets this year, and averaged over the last few years have shown 45% year on year growth. Falcon 9 itself will not continue that growth rate for much longer, but it has initiated a trend which will likely be continued by vehicles such as Starship and New Glenn.

A habitat such as the Bernal Sphere, pictured above, houses 10,000 people and masses at around a million tonnes. At current growth rates, the year our annual mass to orbit rate exceeds this is 2041. If we say only 10% of global capacity can be devoted to it, then the required level is reached in 2047. Note that this large amount of material does not have to come from Earth - over time resources on the Moon and elsewhere will be developed and contribute to the ongoing growth.

So if something like this is build in the 2040s, what does this mean for the UK? Well, it is vastly cheaper to get to. Such colonies would be build in the vicinity of Earth, and could be reached in days or even hours depending on orbit instead of months. Thus, a Starship taking passengers to one would be more like an airliner than a cruise ship in terms of the space required for each person. 250 people per Starship is feasible, reducing seat cost from £2.1 million to £420,000. The number of people who can afford a home in this price range is a lot larger.

If the habitat is build in Low Earth Orbit, which has been suggested even though it brings some technical challenges, then passengers also do not need tanker flights to add additional fuel - a single Starship can take them directly from surface to habitat. That reduces cost by another factor of 7, down to £60,000. The price of a luxury car of the kind you will regularly see driving around the country.

Lets estimate how many people might take up such an offer. I’m going to choose as an approximation to say that anybody able to buy a new car subject to the UK’s luxury car tax (kicking in at £40,000, soon to be pushed up to £50,000) can probably stretch to a ticket. The average new car price is now close to the boundary, so roughly half of new registrations fall into this category, so that is about 1 million people each year. Now, this poll conducted in 2019 found that 18% of Britons would use their savings to go to space, so it looks like we have around 180,000 people each year who can go at this price and would want to go. They might not all stay - an orbital station is fine for a short visit, unlike Mars. So who would move out permanently to make a new life, and why?

A person living in an orbital space station can build space hardware and provide services in space without being subject to the substantial costs and difficulties of launch. It will be a place of immense and exciting economic opportunity, appealing to the most able and ambitious graduates - which may be a problem for an aging and ossifying terrestrial economy that offers them little.

Average graduate salaries are around £34,000 in the UK, so if this group were to leave, that would conservatively take £6 billion from the economy right away - given in the last year GDP grew only by £30 billion, and growth is unlikely to pick up again with our aging population, this is not an insignificant hit. It would also be continuous, as adventurous types from each graduate cohort left for the new frontier.

We must also account for the knock on effects. These people are more likely to be net taxpayers, and if they are willing to move into space they must be risk tolerant and thus more likely to start businesses. New firms currently account for about 40% of job creation in the UK - if we assume from the above survey that the total number wanting to leave, not just those willing to do so out of their own pocket, would attempt to start businesses in space, that would be 29% of 40% i.e around 12% of new job creation would leave.

These are very rough figures - there are a lot of unknowns and its impossible to truly know how people will react to the possibilities of space colonisation until the option is actually available.

After 50 Years

As outlined above, getting to a near Earth colony is a lot easier and cheaper than going to Mars. But there is a way to bridge that gap - the Mars Cycler. This is an orbit that constantly oscillates between Earth and Mars with minimal need for reboosting, on which is has been proposed we build a station for people to live on during their journey to Mars. Not having to take 6 months of living space and supplies with you every time you go means, like the near Earth tripe, you can pack more people into your Starship - it is only a short trip to the cycler station as it passes Earth.

You still need to have as much propellant for any other Mars trip, in order to catch up with the fast moving station. So you only get part of the saving. However, some or all of that propellant may over the next 50 years be sources from the Moon or nearby asteroids for less cost than it could be transported from Earth. 80% of the propellant mass is liquid oxygen, and oxygen is a byproduct of extracting silicon from Moon rocks in order to make solar panels for the nascent space data centre/space solar power industries. It would be produced in such large quantities as to be negligible in cost, so a decent estimate is a 5x reduction in propellant cost, and based on the above calculation that would mean a Mars ticket price of £132,000.

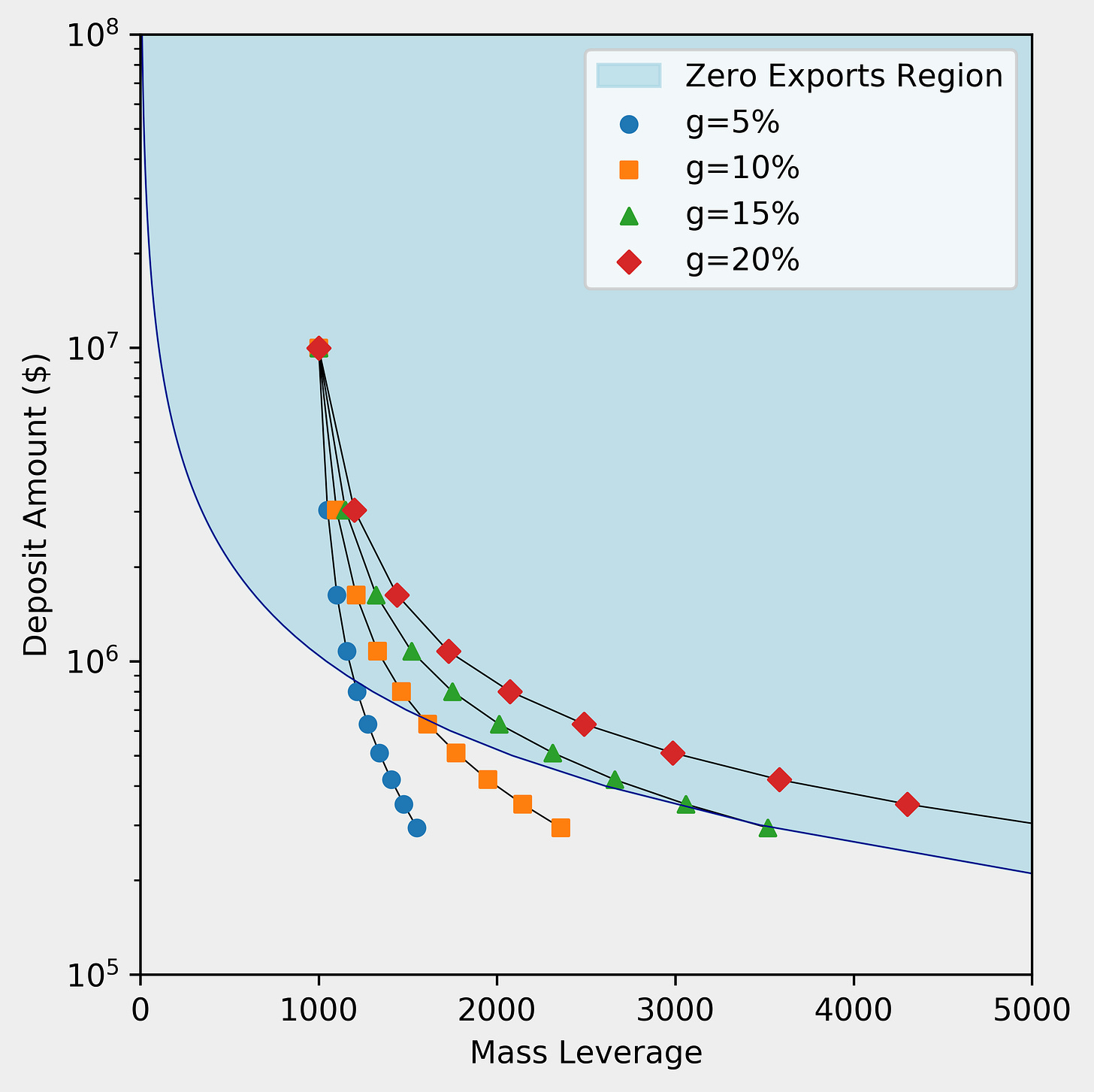

Aside from travel expenses, colonists would also need resupply from Earth for the foreseeable future. An autarkic Mars is quite a long way off, even in the most optimistic scenarios. The good news is that autarky is not needed - colonists leaving their net worth in an endowment when they leave can generate the trickle of supplies needed to keep the colony going, so long as the mass leverage (how many kgs of stuff the colony produces per kg of resupply) gets better at a pace which compensates for the pool of potential colonists becoming less wealthy. I get into the maths of it here but below I’ve reproduced the main plot:

If, through recycling and use of local resources, a space colony can keep in the blue region above - it never needs to export anything to afford the supplies it needs from Earth. If there are any viable exports back to Earth, it just makes the job a bit easier.

There is a possibility of grasping governments, fearing their tax base fleeing, going after the endowment on Earth or the launch companies it pays to send supplies. Hopefully, with multiple territories and multiple launch providers in play, this sort of aggression from the tax man can be countered.

Costs will have to be lowered both to broaden the number of people who can go, and to ensure they have enough left over to fund their slice of a colony endowment. Packing larger groups of people into a Starship, and lowering costs, will make the price of getting to orbit comparable with the price of major life changing transformations on Earth - as I detail in this article

I have covered the theoretical minimum cost of flight to space before. The top line figures are that low single digit thousands of pounds are in principle feasible with rocket technology - and with non-rocket launch methods with don’t require any new physics or unknown materials, hundreds of pounds is possible.

On this timescale, the risk tolerant early adopters of space colonisation will have made the new settlements a lot nicer to live in. Moving out into space will be safer, and the growing population of the destinations will mean they can have more of the specialists that make modern life possible - dentists, lawyers, nursery workers etc. Combined with a low ticket price, there could be a loud sucking noise of net contributors leaving at an increasing rate as bonds issued in the 2020s come to maturity

Pricing the Future

I get no impression that these considerations are taken seriously by institutions buying these gilts. But they should be - and the risks priced in. If you are dealing with such long timelines you need some model of how the world may change over that time, beyond simple actuarial tables.

The alternative, of course, is that the government could simply spend less than it collects in taxes, pay off these long term debts early, and build a long term fiscal foundation for future generation instead of saddling them with debt for short term political gain. This is not the place to discuss such out-there science fiction ideas though - I only write about space colonisation.