Setting Apollonian Goals

How can societies get meaningful things done?

In January many of us set new year resolutions - lose weight, give up a vice, exercise more etc. - and usually struggle to stick to them. It is the same way with societies too - governments announce lofty goals only to swiftly disappoint everybody. Quite often, this will take the form of something being touted as a “moonshot”, and as far as I can tell, every single instance of this has been a failure - with the notable exception of the actual, original moonshot.

A monumental task, never before accomplished in human history, was delivered on time and only modestly over budget through a government program. This would be unusual for something as simple as building a bridge, never mind sending humans to another world.

To see why, first lets go back to the original public declaration of this project:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. We propose to accelerate the development of the appropriate lunar space craft. We propose to develop alternate liquid and solid fuel boosters, much larger than any now being developed, until certain which is superior. We propose additional funds for other engine development and for unmanned explorations—explorations which are particularly important for one purpose which this nation will never overlook: the survival of the man who first makes this daring flight. But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.

President Kennedy, Address to Congress, May 25th 1961

It is worth highlighting a few things in this quote. The objective of Apollo is very clearly specified. But even in this speech Kennedy admits that the US does not yet know how to do this - he mentions that both liquid and solid boosters will be researched as they did not know which would be the best approach at the time. He also mentions unmanned exploration, necessary for crew survival. The conditions in deep space and on the surface of the Moon were not well known at the time, so these were necessary to inform design of the lunar spacecraft.

The why and what are very clear even in 1961, even if at that time there was still a lot of uncertainty around the how.

I believe I have some insight into why this particular task worked so well, compared to others that have been attempted.

Difficulty and Complexity

It is often said, typically after a rocket has violently exploded mid-flight, that “space is hard”. This is evidently true. But it is, at the same time, simple. What I mean by this is that, despite being a fiendishly complicated engineering problem, the objective of a satellite launch is incredibly simple - the payload must reach such-and-such an orbit intact. It takes thousands of engineers to build and launch the rocket, but a single astronomer can verify if it placed anything on the intended orbit or not, and anybody with a suitable radio antenna can verify if the payload is alive and giving off signals.

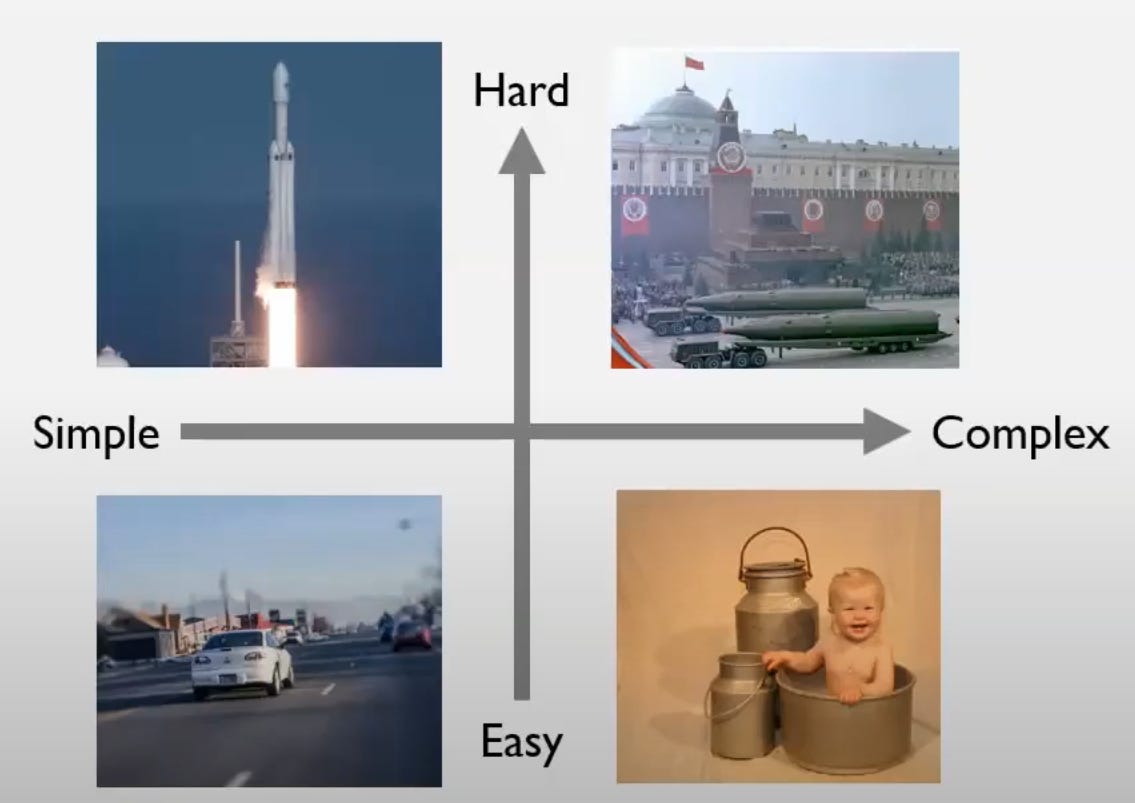

Not all problems are so well defined though. Some years ago I gave a talk at the Mars Society convention where I presented the following taxonomy of problems:

Top left is spaceflight - as mentioned above, a hard problem but simple in that the objective is well defined. Top right is a centrally planned economy - suffering from both a huge amount of moving parts and a complex and poorly defined objective.

Bottom left is commuting to work. Its a well defined task that one person without much training can perform. Bottom right is raising a child, which although consists of many technically simple tasks, is something broad and open ended without an agreed on definition of the “right” way to do it.

If the problem is simple, then there is an ever present criterion on which to assess the merit of any particular action, solution, or component. For instance, the Apollo program was able to settle early on the debate over the type of mission to be flown - direct ascent, Earth orbit rendezvous, or the ultimately chosen lunar orbit rendezvous - before any hardware had been built, essentially from first principles. Projects that did not directly assist with the Moon landing goal such as early space station concepts or extensions to the Gemini missions were ruthlessly culled.

Unintended Consequences

Its not enough, though, to have simple objectives. They must also be the actual thing you want to achieve, not a proxy that can be faked some other way.

There are many anecdotes used to illustrate this problem - for instance, that in British India the authorities offered a bounty for cobra tails to control the population and reduce the number of people getting bitten, only for enterprising locals to start cobra farms. When this was realised and the bounty rescinded, the farmed cobras were released making the original problem worse. There is no evidence this actually happened, but it gets the point across.

In the space sector, one of the worst unintended consequences has been from the use of cost plus contracting. Originally conceived as a way to prevent military contractors from earning excessive profits, it paid them according to their costs plus a fixed percentage. As a result, contractors were incentivised to massively inflate their costs - this process is why the Space Launch System and Orion capsule cost around $4 billion per launch. By contrast, the commercial cargo and crew programs for the ISS delivered much lower costs by offering fixed price contracts for specific deliverables.

Shaping the Future

So where does this leave us now in terms of policy making?

NASAs current Artemis plans, which also include ESA and JAXA, have vaguely defined goals and still include cost plus contracting. In China, the CNSA has set itself the same goal as Apollo in the near term and seems to be doing quite well with it.

SpaceX has a mission statement of establishing a city on Mars, and with it the quantitative goal of a million metric tonnes to orbit as a requirement. This is well defined and clearly motivates the workforce - but it has been questioned how much shifting that much mass to orbit maps to the goal of the city. It is certainly a necessary requirement, but not a sufficient one.

Blue Origin publicly wants to create a “Road to Space”, which is not well defined at all, but perhaps internally they have more specifics about what this “road” looks like. Long term, Jeff Bezos has taken on the vision of giant colonies in space espoused by Gerard O’Neill. This can be used to generate a set of requirements - notably the quantities of mass that need to be moved around, as in the case of SpaceX. If they have a figure in mind, they haven’t publicised it at this point.

What SpaceX and Blue Origin have in common that NASA has not had for a long time is singular leadership - one person at the top able to set the direction of the organisation. Perhaps, under Jared Isaacman, this issue will be resolved and Artemis acquire clear and useful goals.

Excellent use of history to point the way to possible future paths. I would like to see a similar analysis of Vast Space. If I were a betting person, I would bet on Vast Space in the near term, but on Blue Origin over the longer term. Going into space just to go down another gravity well (Mars) to live under conditions worse than Antarctica looks like a terrible bet.