A Polar Solution

Everyone knows the best place to fly rockets from is the equator. Its not quite that simple though...

A few months ago now, I started a petition that asks the UK government to fund a heavy lift spaceport for rockets above 100 tonnes to LEO. It is already UK space policy to provide such launch sites for foreign companies - notably Virgin Orbit - but that case failed because the company was not financially sound. My suggestion is simply to apply the same principle for a much better launch vehicle from a company that is on a more stable footing. As well as serving existing launch markets, I believe that such a location could be used to support a large scale UK space station.

If you live in the UK you should sign the petition and if you live abroad you should send it to someone you know who does live in the UK.

The most common object I get, by far, when talking about this is that the UK is too far from the equator to be a good launch site. It is a common bit of space knowledge that, in order to achieve the speeds needed for orbit, it helps to have a kick from the rotation of the Earth, and that this rotation is strongest when launching east from the equator. Launching north from over 50 degrees latitude seems, in this context, ridiculous.

But the picture is not as simple as that. The USSR ran a robust space program from Baikonur cosmodrome, at roughly the same latitude as Geneva. Furthermore, they also have a northern launch site at Plesetsk which is almost in the arctic circle. The UK itself already has two sites set up for vertical rocket launch to orbit, one on the north coast of Scotland and another on Shetland. So the simplistic picture of high latitude being “bad” is obviously not true.

If launching to a polar orbit, where the plane of the orbit is close to 90 degrees from the equator, the Earth’s rotation is more of a hindrance than a help. If flying to an orbit at exactly 90 degrees inclination, all of the rotation at the point of the launch site must be cancelled out by rocket power. It is perfectly possible then to have an exclusively polar launch site from a place like the UK.

A Place in the Sun

A very useful subset of polar orbits are the Sun-Synchronous Orbits (SSO). The oblateness of the Earth causes precession of orbits, the rate of which varies with inclination and altitude. It was realised early in the space age that choosing the right combination of inclination and altitude could cause the orbit to precess one complete circle in a year - thus meaning the orientation of the orbit when viewed from the Sun would remain constant. Such orbits are usually slightly retrograde of polar - at the altitude of the ISS the correct angle would be about 97 degrees from the equator, so Earth’s rotation is even more detrimental.

The orbital insertion can be timed to pick the exact orientation of the SSO, and one subset of this orbit are the “dusk-dawn” or “twilight” orbits, that appear face on when viewed from the Sun. Above a certain altitude (about 1,300km) this means that a satellite in this orbit will never be in eclipse. As the orbit is still relative to the Earth’s equator, it does have a seasonal “wobble” back and forth though, and this means that around the solstice a lower altitude SSO can have brief eclipses - the calculations are detailed in this document. Generally though, this is an orbit which can get near continuous sunlight, and does not have the regular long eclipse that all other orbits at this altitude have. From a power point of view, this is a good thing as it relieves somewhat the requirements on batteries and the requirements to spend power charging them.

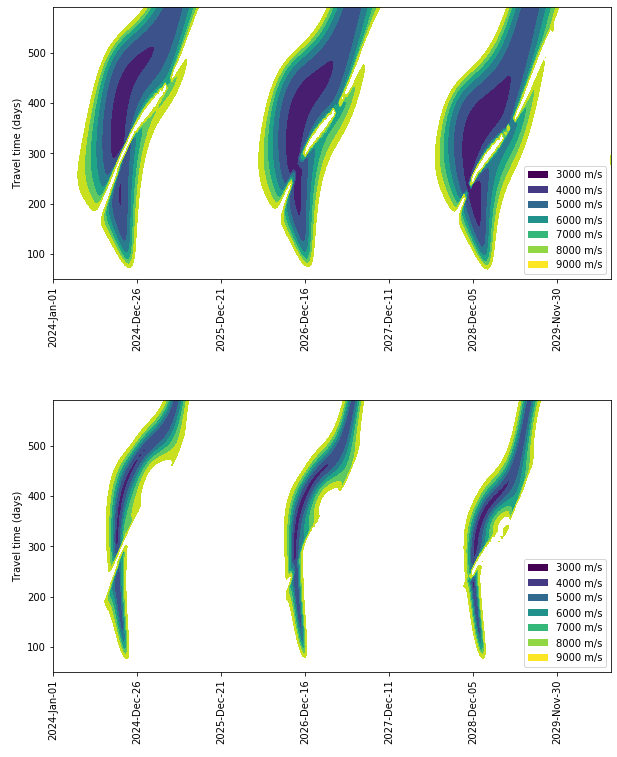

This is all fairly standard stuff - but the dusk-dawn orbit has another feature not as commonly understood: it’s viable for interplanetary travel. The plot below demonstrates how.